A cure to the meth epidemic through spreadsheets

I live in Oregon, the state with the highest per capita methamphetamine use in the nation, as determined through treatment statistics. Meth addiction is a particularly notable problem in my home region of Lane County where Rep. Peter DeFazio recently announced that Lane County ranks second in Oregon for meth seizures. I have seen meth addicts in my own neighborhood, and I wouldn't at all be surprised if those who stole my car last December had meth in their systems at the time.

The Oregonian, a large Portland-based paper, had been reporting on the rise of meth use and related crimes since the drug surfaced in the early 1990s. In late 2001, the newspaper set Steve Suo the task of reporting on what had become a major social issue for Oregon.

Suo visited my Power Journalism class today and explained the path he followed to get to a major Pulitzer-Prize-winning, five-part story on the spread of meth use from its origins in California and the very simple and effective steps the government can take to choke off supplies of the key ingredients ephedrine and pseudoephedrine.

The four-year research effort that Suo has put into the topic has sparked local, national and international actions to cut off the super-labs in Mexico, which manufacture 80 percent of the meth used in the United States. These amazing results – and hopefully more concrete actions soon – have helped to stop the growing epidemic that is devastating some communities.

But how was he able to figure out the clear links between governmental actions to reduce ephedrine and pseudoephedrine on the black market and meth use when policy analysis and government officials hadn't?

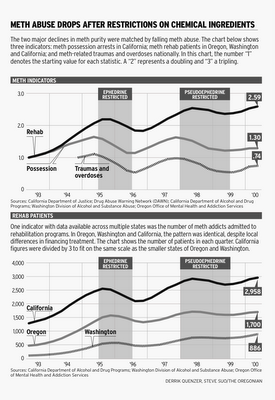

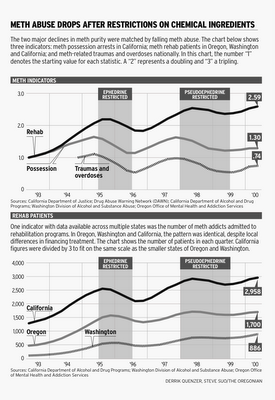

Suo, who had learned a lot about statistics analysis from his graduates studies in Public Affairs, started with a federal study that seemed to indicate that the Oregon Health Plan, which gave free drug treatment to low-income citizens, was responsible for the growing number of treated meth users and didn't necessarily correlate to an increase in meth use. This turned out to be wrong. By analyzing treatment data and meth-related crime statistics from Oregon, Washington, California and Colorado, a clear pattern emerged.

To find the reason for these drops in the indicators of meth use Suo had to dig deeper. He created a timeline of drug busts and congressional actions to restrict ephedrine and pseudoephedrine. Finally, the patterns made sense. One could clearly see that the acts in Congress to restrict the ingredients to make meth, as well as the discovery and subsequent closure of certain pipelines from Europe and Asia led to a massive drop in meth addiction.

It's clear that Suo's efforts and the new ability of print journalists to analyze digital data like professional researchers will dramatically effect the way journalism is done. It used to be that journalists had to wait for government researchers to ask the right questions, conduct their own studies, and release the findings. Today's journalists can add to the wealth of public knowledge by finding correlations that researchers may not see. And the best of them will be able to have the massive impact that Suo did to find a cure for this "Unnecessary Epidemic."

The Oregonian, a large Portland-based paper, had been reporting on the rise of meth use and related crimes since the drug surfaced in the early 1990s. In late 2001, the newspaper set Steve Suo the task of reporting on what had become a major social issue for Oregon.

Suo visited my Power Journalism class today and explained the path he followed to get to a major Pulitzer-Prize-winning, five-part story on the spread of meth use from its origins in California and the very simple and effective steps the government can take to choke off supplies of the key ingredients ephedrine and pseudoephedrine.

The four-year research effort that Suo has put into the topic has sparked local, national and international actions to cut off the super-labs in Mexico, which manufacture 80 percent of the meth used in the United States. These amazing results – and hopefully more concrete actions soon – have helped to stop the growing epidemic that is devastating some communities.

But how was he able to figure out the clear links between governmental actions to reduce ephedrine and pseudoephedrine on the black market and meth use when policy analysis and government officials hadn't?

Suo, who had learned a lot about statistics analysis from his graduates studies in Public Affairs, started with a federal study that seemed to indicate that the Oregon Health Plan, which gave free drug treatment to low-income citizens, was responsible for the growing number of treated meth users and didn't necessarily correlate to an increase in meth use. This turned out to be wrong. By analyzing treatment data and meth-related crime statistics from Oregon, Washington, California and Colorado, a clear pattern emerged.

To find the reason for these drops in the indicators of meth use Suo had to dig deeper. He created a timeline of drug busts and congressional actions to restrict ephedrine and pseudoephedrine. Finally, the patterns made sense. One could clearly see that the acts in Congress to restrict the ingredients to make meth, as well as the discovery and subsequent closure of certain pipelines from Europe and Asia led to a massive drop in meth addiction.

It's clear that Suo's efforts and the new ability of print journalists to analyze digital data like professional researchers will dramatically effect the way journalism is done. It used to be that journalists had to wait for government researchers to ask the right questions, conduct their own studies, and release the findings. Today's journalists can add to the wealth of public knowledge by finding correlations that researchers may not see. And the best of them will be able to have the massive impact that Suo did to find a cure for this "Unnecessary Epidemic."

Comments

Post a Comment